On June 19, 1961 Israel’s Minister of Commerce and Industry and the Minister of Transportation and Communication met in Jerusalem with Leyland Motors’ Secretary for signing a contract for the establishment of a local assembly plant for Leyland products. The plant, co-owned by Leyland Motors and local Leyland distributor CNEC, was to assemble trucks and bus chassis. This was the outcome of the four-year quest for a partner for a commercial vehicle assembly plant in Israel. It was hoped that local content would gradually increase to include production of Diesel engines. The contract with Leyland was a blunt monopoly, where imports of competing products were banned for a period of five years, later to be prolonged.

Not surprisingly, the local distributors were enraged. Jos. Miller, Scania-Vabis’ local distributor for decades, had to confront this potentially-deadly blow. It had also negotiated with the government for a local plant, having in fact suggested a plant already in 1947. Miller appealed to Supreme Court when the initial contract was signed on October 28, 1960, and was given an interim injunction against the contract execution. Once the injunction was revoked, and even prior to Miller’s appeal to High Court (that was later to be denied), Leyland and its distributor were quick to sign the final contract, and get the bulldozers to commence development work in the 120-acre plot in the immigrants city of Ashdod.

The contractual monopoly forced Leyland to promise a quick elevation in local content: up to 50% within five years. The contract’s article 3b detailed the parts to be deleted from the knocked-down kits with assembly start. The No. 1 item was “truck cabs”. That was not a simple task to fulfill. Local customers preferred conventional cabs, and Leyland did not have these cabs available for its Chieftain-Clydesdale range. By the end of September 1961 Leyland’s chief engineers met with the transporters’ union in Israel for a briefing on the desired specs for this market. The British and their local partners could only apologize and utter that “other truck manufacturers are also going the Leyland way and produce similar cabs”. The people demanded a bonnet.

On May 12,1962 a launch ceremony took place in the Merkavim plant in Petah-Tikva. A locally-made champagne bottle was broken against the bonnet of the very first Super Beaver produced in Israel. Merkavim, a bus body producer that had already produced cabs for Volvo L465 trucks, was a natural partner for Leyland until the new plant started operations in February 1963. But whereas the Beaver had an easy-to-manufacture cab, the lighter trucks posed a real challenge. The Vista-vue series cabs, also commonly named LAD for their users (Leyland, Albion, Dodge) included an angular metal cab, linked to a metal skeleton. This was far beyond the manufacturing capabilities that were economical given the small scale of production, a few hundred units a year. Leyland had to find a glassfibre replacement. This cab emerged from Brussels.

The glassfibre-made Europ was utilizing Vista-vue's steel skeleton

Frères Brossel was a bus and truck producer based in Brussels. It was established in 1912 and had to gradually let go of its independent designs, in favor of Leyland-based ones. In 1968 it was absorbed into Leyland. Earlier, in 1961 Brossel launched a new range of trucks with 12-19 ton GVW that was “developed to meet the common market regulations”. The new truck series, badged “Europ”, was actually a glassfibre cab, modeled after the Vista-vue, and placed over the familiar Leyland components. Interestingly enough, the November 1961 French brochure was printed in the UK, and borne a Leyland sequential “leaflet No.”. This most probably points to Leyland’s strong involvement in the design of the Europ, and may also indicate that the Europ was Leyland’s reply to the European common market. The cosmetic updates to the LAD cab – quad headlamps, an external step and a massive front bumper may hint to the changes mandated by the European type approval regulations. It can be safely assumed that the cab material was chosen for the very same reasons it was required in Israel- small-series production.

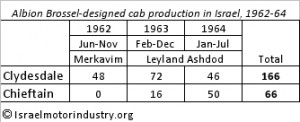

The Brossel Europ along with its Vista-vue inherited steel skeleton was to become in Israel, as of May-June 1962, the Leyland Clydesdale. The Clydesdale, badged Albion domestically and Leyland in some export markets, was the only available truck in its class in Israel, and 43 units were registered by November 1962. Most of the chassis were equipped with a closed box or an open deck superstructure, and some were used as tippers. Two units were assembled as tractors, and Ronny Sharon recalls both were operated by another monopoly, Blue-Band margarine of Haifa. Production in the new plant in Ashdod commenced in February 1963 and by the end of August some 59 Clydesdales were assembled there. The Chieftain was assembled in Leyland Ashdod as of September, initially from kits imported already in the first half of 1962. By July 1964, a total of 66 Chieftains were completed.

A Haifa-registered Clyde in distress. Note no usage was made of the roof window. Photo: Itzhak Sa'ad

In June 1964, the transportation companies were still demanding structural changes in trucks’ design. On July 14 the Minister of Transportation visits the factory and is advised that Chieftain and Clydesdale trucks “have undergone adaptations for the transport conditions in Israel…so that there was a delay in their delivery”. Registration database hints that while this statement was given, the last Brossel-cab Leyland had already been assembled.

In August 1964 the Chieftain-Clydesdale prices increased. Series production for bonneted versions probably started shortly afterwards, during September. This bonneted cab was designed in-house, by Leyland Ashdod’s engineering department led by Rami Ezroni. This cab, produced locally by Or-Lite of Nes-Ziona, will have adorned over 2,300 trucks assembled in Ashdod over the next ten years. It became a prominent Leyland trademark in Israel.

My sincere gratitude for George Burt, who provided me with the key for this enigma.