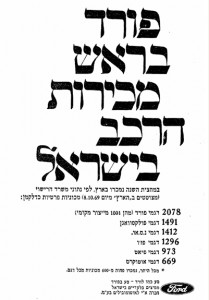

Nice weather awaited the dignities that arrived on Wednesday, 22 May 1968 at the Automotive Industries plant in Nazareth Illit, for the inauguration ceremony of the new Ford Escort, made in Israel. The ten cars on display, all painted white, were about to be delivered to customers in the coming days. By the end of the calendar year production totalled 970 units. This impressive figure, directly linked to the high demand for the Escort, was a unique phenomenon in the local motor industry panorama. Also outstanding were the arrival of the Escort in Israel only four months after its launch in Europe, the fact that for the first time in a decade at least, this was the right product for the car buyers public in Israel and lastly that the entire process, starting with Ford’s announcement of its car assembly plans in Israel up till the actual start of assembly, was extremely rapid.

Henry’s word

In early June 1966 Dr. Shaul Lifschitz, general manager and co-founder of the Palestine Automobile Corp., the local Ford importer, returned from a regular visit to Detroit. He brought home a promise to establish vehicle assembly in Israel. And although this now sounds like a significant statement, in hindsight it should be read differently.

Ever since the car market in Israel has been opened for free (if very expensive) purchase of new cars, in October 1960, car manufacturers swarmed from all over the globe offering their goods. Some were esoteric and minute, other stronger and more impressive. They all wanted to enjoy the benefits given at the time to the local assemblers that were no more than tax shelters. The governmental control over the formally-private sector of car assembly was given to the “inter-ministerial vehicle committee”, in which officials from the finance, industry and commerce, and transport ministries took part. In October 1964 the committee established a sub-committee, headed by Avigdor Bartel, who then headed the Petrochemical Plants. The Bartel committee, officially named “the committee for the evaluation of vehicle and parts production and imports”, was to bring some order to the patchy government policy. By the end of May 1965 the Bartel’s committee concluded its meetings. It was trying to balance the market needs as it understood them, and the continuous pressures of the importers, that called for local assembly – tax-protected naturally – for all. The solution, so it was hoped, should be found within the existing assembly plants: the market’s segments would be divided in a pre-ruled fashion (as was prevalent in the Warsaw pact market, interestingly enough), and the assemblers should continuously aim at increasing the local content. At a government discussion in August, Finance minister Sapir announced, on behalf of the economical ministers committee, that given the Bartal conclusions it was decided “to try and convince Illin and Shubinsky to merge their plants for the benefit of the economy and the consumer”. In spite of the basic solidity of this attempt, it was doomed right from its inception – Illin and Shubinsky refused to meet each other, let alone discuss a potential merger.

Ford did not assemble vehicles in Israel previously, but got close more than once. In 1949, as the first U.S. financial aid to Israel was announced, Henry II sends his guys to Israel in order to explore the option of an assembly plant. In 1950, Ford actually signs a contract for the set-up of such a facility, with the above-mentioned Dr. Lifschitz and his partner Arieh Lowenstein. In complete opposition to his late grandfather, Henry Ford, who freely publicized his anti-Jewish prejudices and went as far as printing a modern version of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion”, bearing his name as the writer, Henry II (Ford’s president since 1946) did his best to publicly support the young country: much-publicized donations, encouragement for new vehicle sales to Israel and as mentioned – serious progress towards establishing a first vehicle assembly plant in the Holy Land. This market’s scope, it should be mentioned, was about a tenth of that of the Arab states at the time. “Ford”, a speaker for a Detroit-based Jewish organization said at the time, “thought of the market in Brooklyn, not Tel Aviv”. But in spite of his good will, Ford could not have promised the future Israeli plant any export markets, simply because Ford was already globally operating wherever new vehicles were sold. It was exactly this promise that a young American car manufacturer could make. In June 1951 it was the Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion who cut the ribbon in the inauguration ceremony of the Kaiser Frazer of Israel plant, 80% of which were held by a group of Israelis led by local entrepreneur Ephraim Illin.

Another venture with Ford began in 1957. Yitzhak Shubinsky has just purchased a share in “Auto-Cars Co. Ltd.”, added up the local Ford importer, Palestine Automobile, as a partner, and convinced the technology provider in the UK, Reliant of Two Gates, to design a four-wheeled vehicle that would match Ford’s powertrain. Production of the Sussita’s forbearer, Reliant Regent IV, starts in Haifa in September 1958. For the next seven years and a half, Palestine Automobile provided no less than 14,000 kits imported from England for the assembly of Autocars light commercials and cars. It also dealt with Autocars’ products marketing, distribution and after-sales services. Shubinsky, constantly aspiring to grow, replaces in late 1965 the indirect Dagenham link with a British giant. Standard Triumph International, a subsidiary of Leyland Motor Corporation, itself already with a state monopoly for the assembly of trucks and bus chassis in Israel, signed up with Shubinsky, along with a new group of partners, to take over the Ford dealer’s shares. The Leyland agreement did substantial damage to Palestine Automobile, as Autocars products formed a large slice of their activities. For instance, 61% of the vehicles sold by the Ford dealer during the 1965 model year were Autocars products. These were cheaper vehicles than the comparable Ford products, but it was obvious that the loss of Autocars could not be taken lightly.

Getting Ford back in Israel

With the Autocars contract coming to its imminent end, Palestine Automobile gets Ford to the entrance gates of the local assemblers. As mentioned, Ford was not the first to grant the Israeli Government the extraordinary rights of paying for its produce without charging the full taxes for it. But Ford is not Saab, Simca or Alfa Romeo. And when Henry Ford makes an offer, one listens. On 8 November, 1966, well into the deep recession, the inter-ministerial committee accepts in part the Ford offer that was presented by Palestine Automobile in conjunction with E. Illin Industries. The offer for assembly of the Ford Anglia cars and tractors was approved, and that for the assembly of vans, pick-ups and light buses (all bearing the Transit logo) was finally rejected two months later, in January 1967.

This was logical, at least given the committee’s centralistic philosophy that called for a market with zero internal competition among the assemblers, but with as wide as possible a representation for various automotive products. Loyal to the obsolete engine size classification for cars, and payload classification for commercials, the committee approved the “10hp” (for its 998cc engine displacement) Anglia, and declined the Transit, that would have been in direct competition with Dodge Trucks, already approved for assembly in the recently-established Automotive Industries (AIL) in Nazareth. The extent of absurdity can only be grasped in retrospect. Ford Anglia was just before retirement. Its production in England ended in late 1967, and on January 1968 the Escort was launched – with a 1100cc engine, a four door on the horizon and a direct and immediate competition with Autocars’ Triumph and Illin’s Contessa. But from a committee that ruled in favor of enlarging the engine size for the Triumph 1300 in order to prevent competition with the Contessa, a more reasonable decision can hardly be expected.

Illin or Automotive Industries?

The co-operation of Palestine Automobile with Illin Industries was not surprising. Autocars had by now become the direct competitor, while AIL, who in November 1966 started assembly of the Dodge WM-300 and D-400 for the Israeli MoD, were not considered experienced enough, definitely as far as assembly of passenger cars for the general public was concerned. But above all, Illin was eagerly looking for a future flow of CKD kits for popular cars. In spite of Illin and Hino’s denials, the future of the Hino’s light vehicles – the popular Contessa and the Briska pick-up – did not look particularly promising ever since the start of negotiations for the merger with Toyota, in 1965. While Hino was much dependent on the Israeli market, where it sent during 1964-66 no less than 54% (!) of its total car exports, Toyota’s focus was at the Arab markets. The Arab Boycott league’s threats made their work, and other than Fuji Heavy Industries and its Subaru, no Japanese car manufacturer had its cars exported to the port of Eilat till 1982.

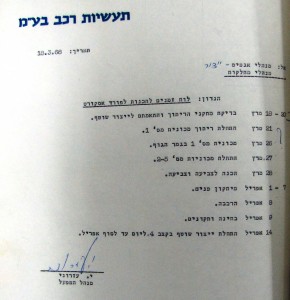

The committee’s announcement did not appease Lifschitz and Illin. Both rushed to the press and declared that “the Government’s decision to approve [the assembly of] one model only does not enable the enactment of the contract”. As a compromise, they offered the government the assembly of the Ford Falcon, a natural replacement for Studebaker’s Lark, the last kits for which were sent to Haifa in 1965. On 2 April 1967 Palestine Automobile management mails the Transportation Minister a request to re-consider the Ford Transit issue. By the way, Lifschitz and Lowenstein do not forget to hinder any possibility that Chrysler-made cars will be assembled in AIL “…we see it clearly that should the Nazareth plant be authorized to assemble [Plymouth] Valiant cars, Ford will regard that as an unfair move”. Slightly over a month later, this clash was a thing of the past. On 12 May 1967, Palestine Automobile signs a deal with AIL, at the latter’s offices, for the assembly of the Ford (at the time still “Anglia”), in Nazareth.

Escorting the growth

Period newspapers do not elaborate much over the reasons behind the last moment’s preference of Joe Boxenbaum’s AIL over Illin Industries. Automotive had an all-new plant with a modern paint shop, and Ford opposed to local manufacture of the fuel tank and the exhaust system, that Illin requested. This can most probably be added to Illin Industries’ eclipse, forced to sell that April its machinery production plant in Ashkelon to Israel Military Industries, and suffered from problematic labor relations since April 1966, when it had to cut its workforce time and again. Given Illin’s location at the Haifa port, and that of AIL at the new development town of Nazareth Illit, Illin’s letter, dated March 1965, to the then Minister of Finance, makes an interesting reading: “the disrespect towards work and the absence rate are over the top…and I cannot see this improving in the near future…there is I believe only one remedy and that is scattering the industry and enlarging the plants at the development areas”.

From this point on Illin and AIL’s ways progress rapidly, if in opposite directions. While AIL’s personnel are undergoing training in Ford Europe and are working in full steam to “pace up the preparations for the Ford Anglia”, Illin Industries goes from bad to worse. The Contessa assembly ended in March 68, as supplies were depleted. Illin makes some further cuts, and appeals to the government in requests, all turned down, for the assembly of Alfa Romeo Giulia (“will compete with Autocars’ Triumph”), AMC Rambler (“too large”) and the Opel Kadett.

In September 68 Illin signs a renewed labor agreement, but there is virtually no work, and the plant produces 2-3 Jeeps a day, compared with 16 in the past, At the beginning of January 1969 Illin sends (not for the first time) 300 dismissal letters, but these are collected and returned to their sender. After simultaneous negotiations, with a prospective buyer on one hand, and with the Haifa workers’ council on the other, Autocars is purchasing the plant on 12 March 1969. As is usually the case at Autocars, press releases as to the brilliant future now awaiting the plant are not reflected by actual performance. Illin Industries, now renamed TIL, receive the Triumph assembly that never went beyond 1,010 units a year, in addition to the CJ-5/CJ-6 production. Two years and a half later, Autocars is bankrupt as well.

And in a symbolic contrast to Illin Industries and its Contessas’ fate, the first Escort goes down the line in Nazareth on 8 April 1968. This Escort, painted Grey and with a red interior, bears identification number DS42CH10001 and will be registered in Tel-Aviv the next month as 250-309. By the end of its assembly in Nazareth, 13 years later, another 27,604 Escorts will have been put together there, a figure that will make the Escort the most popular vehicle ever assembled in Israel.