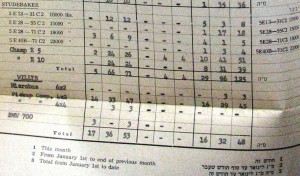

In April 1963, amongst Studebaker Larks, Jeeps and Willys, a small car rolled off the assembly line of E. Illin Industries in Haifa, bearing the Blue-White logo of the State of Bavaria at its front: a BMW 700 Luxus. Over the next month another three cars were assembled there, and that was it for a locally-made Bimmer.

How did these BMW make it to Haifa? The story takes us back to the early Fifties.

Not living in a bubble

Ephraim Illin, already with international trade experience and one of the owners of the Fiat distributor in Israel, inaugurated Kaiser Frazer Israel (KAFRIS) in 1950. In mid-1951 the plant started the assembly of American cars, compact and large ones. The local Israeli market was small, new car purchase was strictly controlled to prevent hard currency running out, and Illin has to export. In 1955 he was able to obtain an assembly contract with Renault, one that provided the plant with products slightly better tailored to the Israeli market of those days.

Following the Suez crisis in late 1956, the European bubble car producers became ever stronger. This idea appealed to Illin as well, as he felt the need to offer a line-up better suited to local requirements. In September 1957 Illin prepares an exposé to the Trade and Industry minister, headed “Production of a small popular car in Israel, within the framework of the industry development in the Southern city of Sderot”. That was a grandiose plan for a midget vehicle, the French version for the Isetta. According to this plan no less than 1,200 units a month (!) would have been produced in Sderot by 1959. The plan soon fell through, and in 1959 the contemporary star at Illin’s was the inaptly named Noble, another ridiculous bubble car, this time of English roots.

Hit by the French and the Austrian

As the 1959 vacances were over, Renault refused to ship further CKD sets to Illin, and sent a termination letter in October. The need for a small car has now become critical. The third reincarnation of Illin’s popular car included a bubble-made-family car with four doors, acheived without detracting from the only real advantage of this concept – a low price. The result was ridiculous: the French stylist penned an ugly steel shed on wheels, justifiably earning a mocking article by a leading writer. The prototype was celebrated in Israel in 1961, but just like Renault, the earmarked engine supplier, the Austrian Steyr, advised Kafris that summer that it could not keep its promise, threatened by the Arab boycott league. Illin called Munich for help, asking BMW to provide it with engines for its “Popular”.

Meanwhile, in Munich

The late-Fifties BMW was not the legendary sportscar manufacturer of the late-Thirties, and surely not today’s superbrand. It was a bruised corporation, whose historical R&D center in East Germany was nationalized by the Soviets, and with a confused product line-up that started with the license-built Isetta and ended with elite vehicles produced in small numbers and sold at a loss. BMW also offered the 600, its own interpretation for a slightly larger Isetta. In September 1959 BMW launch its 700 model at the Frankfurt show. Initiated by the Austrian importer, it was an upgraded 600 boasting a modern, spacious and elegant body designed by Michelotti. But BMW ran out of money and at its shareholders’ meeting in December the board asked for the approval of a sale to the Stuttgart giant, Daimler Benz. This sale would have probably taken place unless for one shareholder named Herbert Quandt, that increased his holdings in the Bavarian company. BMW survived, and the 700’s success provided it with enough fuel to grow over the coming decade. In a similar fashion to other manufacturers, the new BMW was maximizing its sales through the distribution of CKD kits in markets where this proved financially beneficial.

Tax shelter benefits

In September 1960 Auto-Stock, the then BMW importer, started sales of the 700 model in Israel. The elegant car won immediate success, and 376 units were retailed in 1961, an impressive figure. Maybe as a result of the search for his Popular car’s power source, Illin provides in August 1961 the inter-ministerial vehicle committee with a proposal for the assembly of BMW 700.

Over the next few months this proposal earned a considerable amount of the problems that marred the Israel Motor Industry throughout its lifetime. These were strong government involvement, a paralyzing dependence on subsidies, the producer’s enthusiasm over an apparently easy-to-get market and in the bottom line – too little local content.

Who got the cream?

Together with BMW proposals were also made by the German Glas (Goggomobil manufacturer), Morris and Standard. The latter has just entered the lap of Leyland Motors, already having an assembly contract in Israel. This did not make it any easier for Illin, who had an expiry date set for September 21. The three economical ministries explain, over the press, that “the government has no intention to give the producers any tax protection”, and most graciously offers Illin to ask BMW for more time. A few days later the three ministers decide not to accept Illin’s request.

A week later the picture gets clear. On 1 October the daily “Davar” reports that the general view of the committee is that the Standard proposal is better than the others and adds that “it seems that if Leyland is to hand a serious offer, fit for the market conditions, it will have an advantage over [other] assembly proposals”.

A chronicle foretold

That was well expected. It was as recently as on 19 June that the Government signed a contract with Leyland for the assembly of trucks and bus chassis in Israel, granting the British with monopoly rights in their segments. Although it was not clear how Leyland could keep its promises with regard to accelerated local content, it has enjoyed over the next ten years a nearly magical influence over the Israeli governments, as long as it agreed to openly co-operate with Israel. A short visit to Jerusalem of one of its executives and a hidden threat was enough to keep the government’s eyes shut on the belated deliveries, the preference of imported parts and the export promises, usually not materialized. Sapir, the strong man in the Israeli economy at the time, put it very sharply: “Leyland came to our footstep when we were lonely. Even if we are better now – the contract cannot be broken.”

And indeed, four years later it was Leyland who made a contract for car assembly in Israel. But let’s go back to Illin, BMW and 1961.

Morning training and a currency devalued

No Israeli market rookie, Illin signed the contract with BMW in January 1962, without receiving any tax benefits. The Israeli plant was to assemble at least 840 units a year (a realistic figure, it should be mentioned), while local content will be subject to pre-approval of the Bavarian producer. Earlier, in late 1961, a few sets were imported “for training purposes”.

In February 1962 it all came to a halt. Sapir announced a new economical plan, and devalued the Israeli pound by two-thirds. As the local content of the future 700 was very low, this devaluation had a strong effect on the sales forecast. Illin had to re-do their homework, and asked BMW for a prolongation of another six months. But then it turned out that not only the devaluation was standing in Illin’s way to making BMWs. In order to be granted any tax benefits, the local content had to reach 25%. This, in turn, meant the rear axle and the propshaft were to be locally made. With a new machinery plant, Illin was well equipped for the job, and it can only be assumed that BMW was less enthusiastic.

That was the end of the short BMW-Illin affair. The four CKD kits imported in 1961 were stored till March 1963. Only then it was decided to assemble them, and market them locally. None survived.

Final chords

It appears that BMW did not give up so easily on its plans for the Israeli market. In May 1963 Illin finally got hold of a contract for a small car, that of the Japanese Hino. His Contessa posed a real threat to all involved in the local market – importers and assembler alike. Autocars’ co-owned and director, Yitshak Shubinsky, by then already an established assembler, reacts a month later with a letter to the authorities. Through the colorful wording it is quite easy to see his anger: “If your policy is aimed at the increase of distortion and that of the imaginary Dollar savings doctrine, we have no choice but to go your way and assemble foreign cars in our country”. Shubinsky then added that a month ago he made contact with BMW’s export manager, Horst Herbstreit, who advised him that BMW is willing to have a “close co-operation with immediate effect”. The Autocars letter was accompanied with a request for import license for complete cars and CKD kits.

For the time being, Shubinsky was left with the glassfibre and in July 1965 advised the press of a contract with BMW, according to which the German brand will provide Autocars with the powertrain for its 700, while other components will be made in Israel, along with a glassfibre body. In parallel, an interesting guest was shipped to Tirat Carmel – a BMW 700 Cabrio. Ze’ev Weishaus, the then production manager at Autocars, said the company was about to produce this 700 as a Sabra Sport replacement. BMW, which just ran out the 700 production, was willing to transfer to Autocars the rights for the body production as well as its export markets. In December, Leyland signs a memorandum with Autocars and this BMW project is mothballed, too. The 700, 1500 and the models that followed them continued to be shipped from overseas.